With Patience & Dignity

With Patience & Dignity

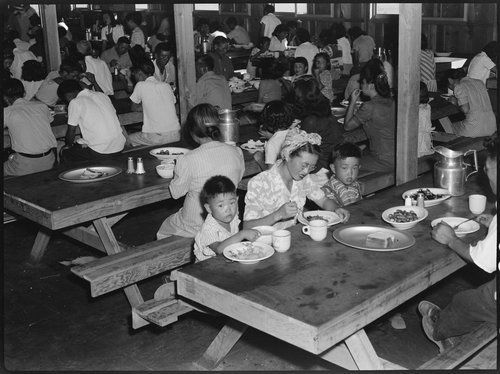

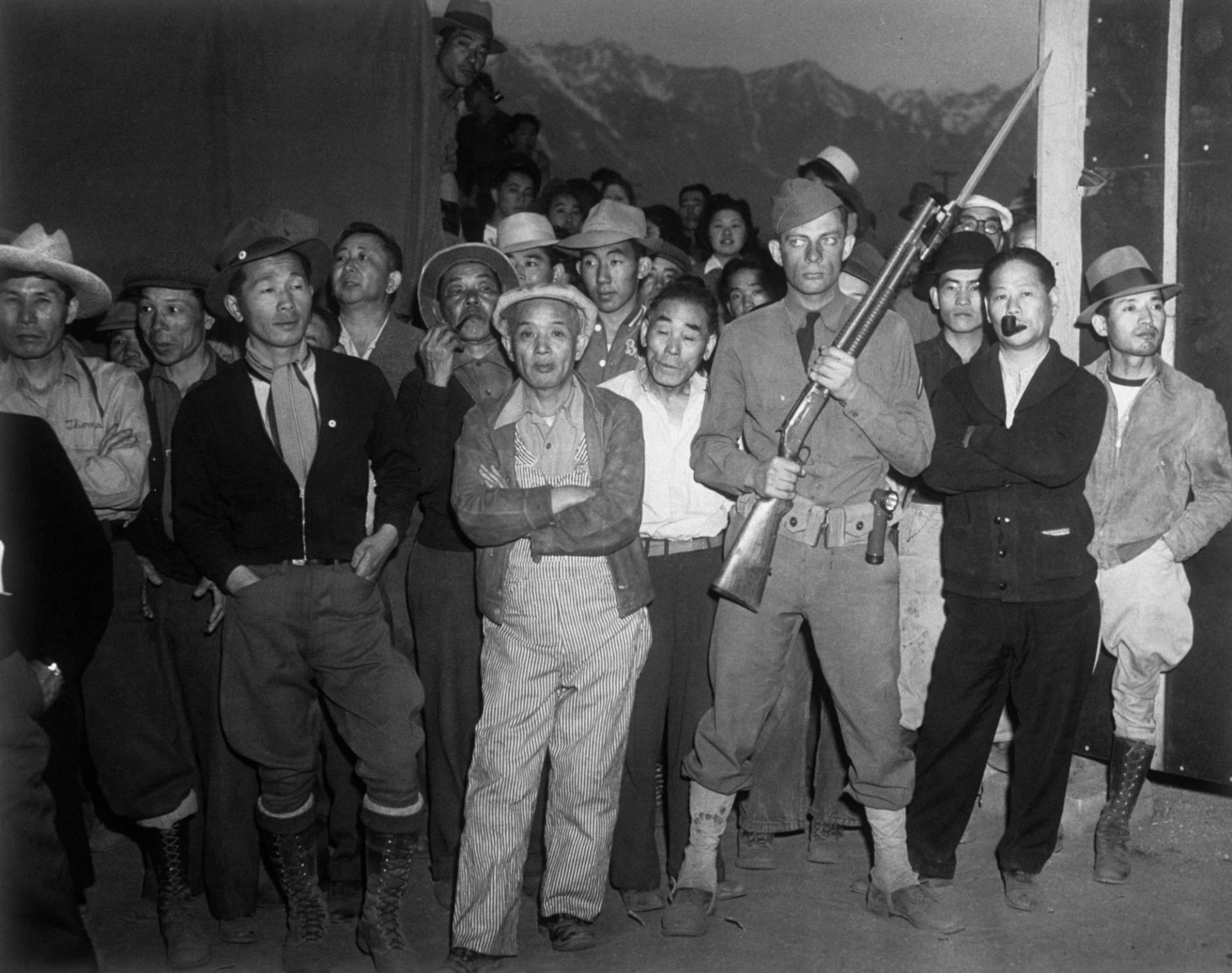

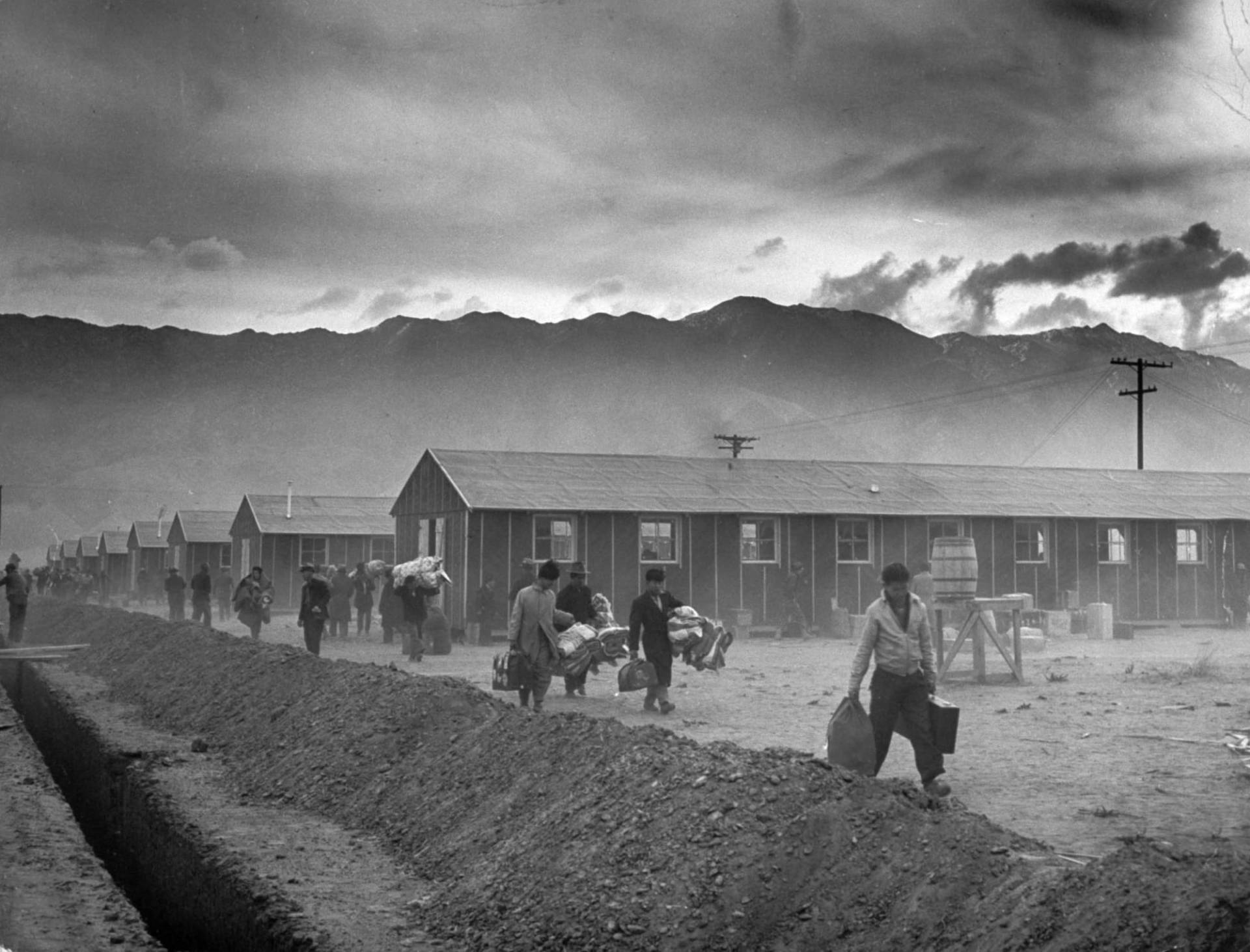

Japanese Americans were forced to deal with the stress of enforced and immediate dislocation and the abandonment of their homes, possessions, established roles within the communities, and businesses. They were not granted any information regarding where they would be taken, how they would be treated by the government, or how long they would be gone. On top of this uncertainty of their safety and future existed the larger psychological burden of being stripped of their civil rights and the unjust accusations of disloyalty. Within the camps, the conditions were dehumanizing; feelings of helplessness emerged, naturally, under the prison-like circumstances. Some of the internees became angry and resentful about their unjust imprisonment while others attempted to make the best of their situation, responding with the Japanese cultural notion of gaman, meaning to bear the seemingly unbearable with internal perseverance, patience, and dignity.

Japanese Americans were forced to deal with the stress of enforced and immediate dislocation and the abandonment of their homes, possessions, established roles within the communities, and businesses. They were not granted any information regarding where they would be taken, how they would be treated by the government, or how long they would be gone. On top of this uncertainty of their safety and future existed the larger psychological burden of being stripped of their civil rights and the unjust accusations of disloyalty. Within the camps, the conditions were dehumanizing; feelings of helplessness emerged, naturally, under the prison-like circumstances. Some of the internees became angry and resentful about their unjust imprisonment while others attempted to make the best of their situation, responding with the Japanese cultural notion of gaman, meaning to bear the seemingly unbearable with internal perseverance, patience, and dignity.

Photos courtesy of Dorothea Lange and History.com

Gaman

Within the Fences

Gaman

Within the Fences

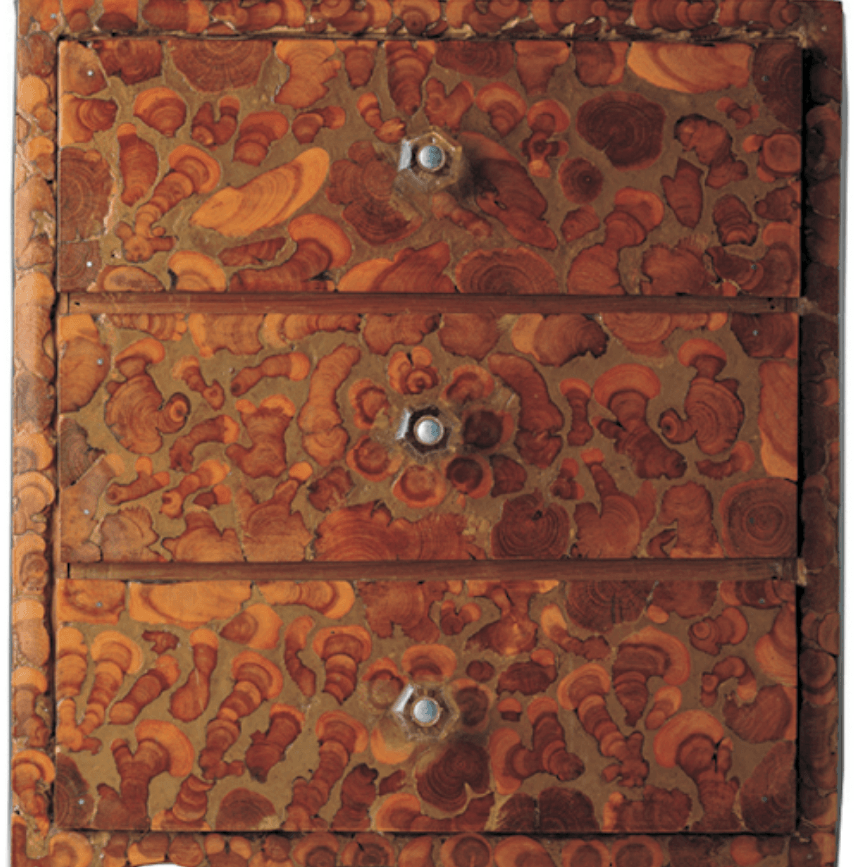

With nothing to connect them to their old lives, the internees crafted objects that gave meaning to everyday life, persevering for years with the utmost dignity and patience- a strong spirit of gaman. The objects allowed them to maintain a sense of self, express their emotions, and reveal what really happened within the barbed-wire fences. Because the internees were only allowed to bring with them what they could carry, they lacked any sort of personal belongings in the camps, leading to the crafting of objects out of necessity.

Photos courtesy of Delphine Hirasuna

Objects Crafted Out of Necessity

The point is not simply the artistic integrity of the objects, but the story of their use. These were not trained artists- they were real, regular people who crafted everyday things out of necessity- furniture, tools, toys, teapots, games, instruments, pins, ornaments. Nothing was thrown away without first being scoped out for its craft/art-making possibilities. And so, in all ten of the internment camps, people began making whatever they needed with what materials they could find around them. Scrap lumber became furniture, found metal was turned into knives and tools, and for fun, scrap wood was carved into small, painted objects. This thrifty spirit is consistent with gaman, as the internees made use of what little things they did have in the camps in order to triumph over the adversity (Hirasuna).

Across the many interpretations of gaman, it has often been interpreted by Nikkei and non-Nikkei as “a call to quietly accept oppression, especially in relation to ‘camp’” (Shimabukuro 650). The internees’ acceptance of their oppressive circumstances- the conviction of shikataganai- is evident in objects like small geta and walking cranes; rather than retaliate against their situation, they created the necessary tools to ease their experience. Objects like the canes and geta tell the story of a lack of vehicles in the camp; the internees had to walk everywhere on unpaved, sandy paths, so these objects were an everyday necessity. As eight of the ten camps were located in the desert (and two were in swamps), the abrasive sand and swampy muds made the shoes essential to their daily lives. Rather than use their resources to create weapons for retaliation, the objects allowed them to accept their situation peacefully, under the acknowledgement that “it cannot be helped”, so they had to help themselves.

Beautiful Objects to Cope

With the passivity to cope with adversity also existed strength in the patience and perseverance of the internees. On top of creating objects out of necessity in order to endure the maltreatment, the internees created art to amuse and express themselves, as there was little to do due to their lack of freedom. The creation of beautiful art and objects allowed the internees to bear the catastrophic circumstances that they had no power in changing. Throughout all of the camps, “sumi-e brush painting, ikebana flower arranging, whittling, haiku writing, and drawing” were popular ways to pass the time and satisfy a desire for beauty in such desolate environments (Hirasuna 359). Across all mediums, there is consistency in the amount of detail, a certain level of intricacy that can only come from time and focus. This portrays the spirit of the internees despite their harsh living situations; the time, patience, and care it must have taken to create such objects are the physical manifestations of their gaman, shikataganai, and gambatte

mindsets. Most of these artists did not continue with their artistic endeavors once they were released from the camps, supporting the idea that the intricate creations were simply a temporary way to patiently survive the imprisonment. The internees channeled old cultural convictions like gaman

during a time of extreme adversity in order to survive those rough years.

Inward Perseverance, Outward Silence

Such cultural notions of patient persistence influenced the internees to maintain outward silence and inward reflection. The internees saw outward complaining as an addition to the struggle that would worsen the experience for those around them and themselves. Rather than express outwardly about their personal and communal struggles, the internees utilized their surroundings to create objects and art that allowed them to privately work through their emotions. This creating-to-gaman

speaks to the use of the quiet technology of artwork to privately organize one’s emotions and thoughts; the created objects helped the internees quietly cope. As a result, hundreds of objects, works of art, and photographs are left over from the internment camps that accurately reflect the emotions of the prisoners. Now, even if the survivors are reluctant to speak on their experiences due to their strong convictions of gaman, the objects created as a manifestation of gaman

during the war may tell their stories.

“ I remember thinking, ‘Am I a human being? Why are we being treated like this?'”

- Albert Kurihara, Santa Anita Assembly Center

“We couldn’t do anything about the orders from the U.S. government. I just lived from day to day without any purpose. I felt empty … I frittered away every day. I don’t remember anything much… I just felt vacant.”

- Osuke Takizawa, Tanforan Assembly Center

"We were going to lose our freedom and walk inside of that gate and find ourselves cooped up there… when the gates were shut, we knew that we had lost something that was very precious; that we were no longer free.”

- Mary Tsukamoto

"I tried to make the best of it, just adapt and adjust.”

- Mine Okubo, Tanforan Assembly Center

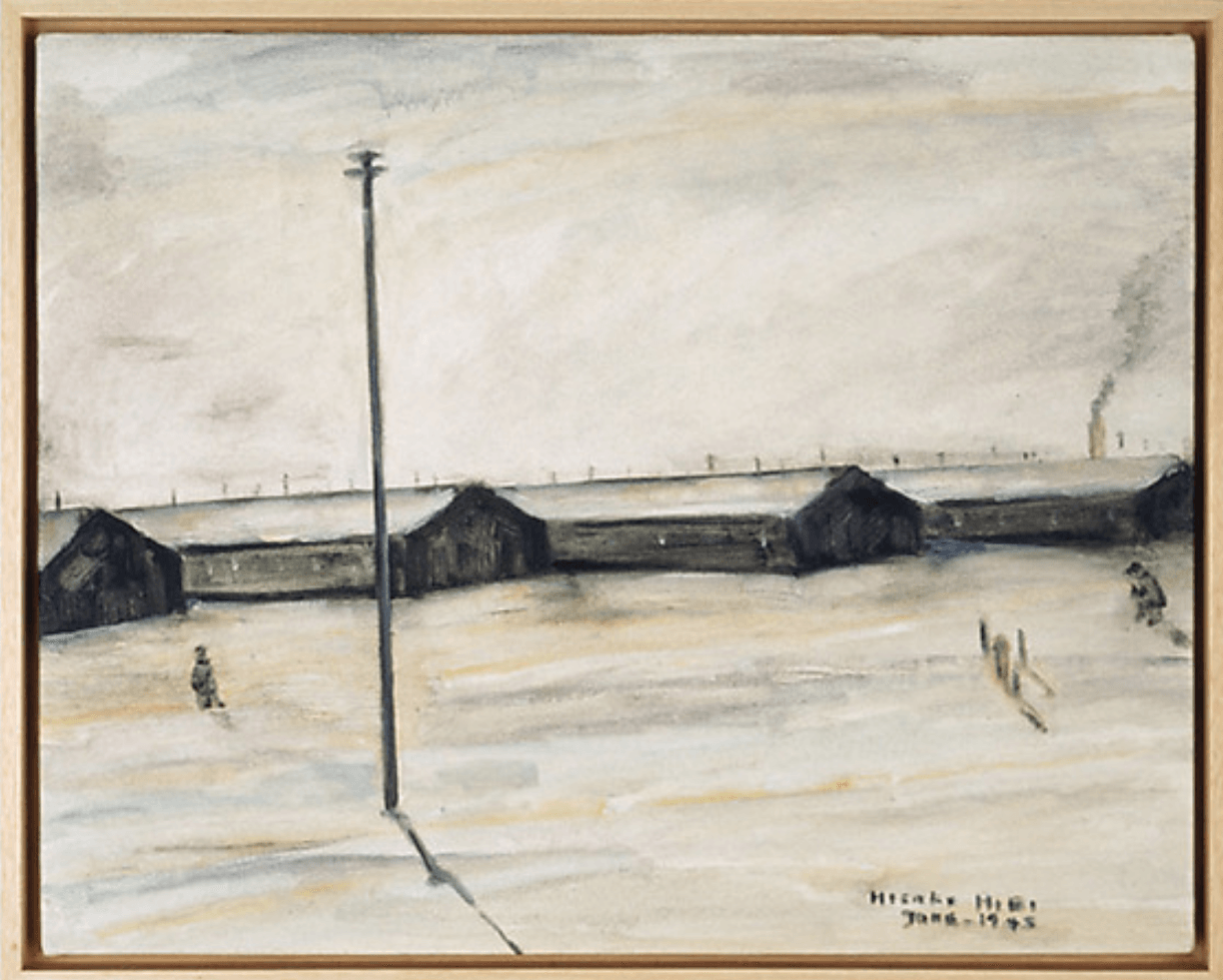

Hibi, Hisako. White heat. 1943.

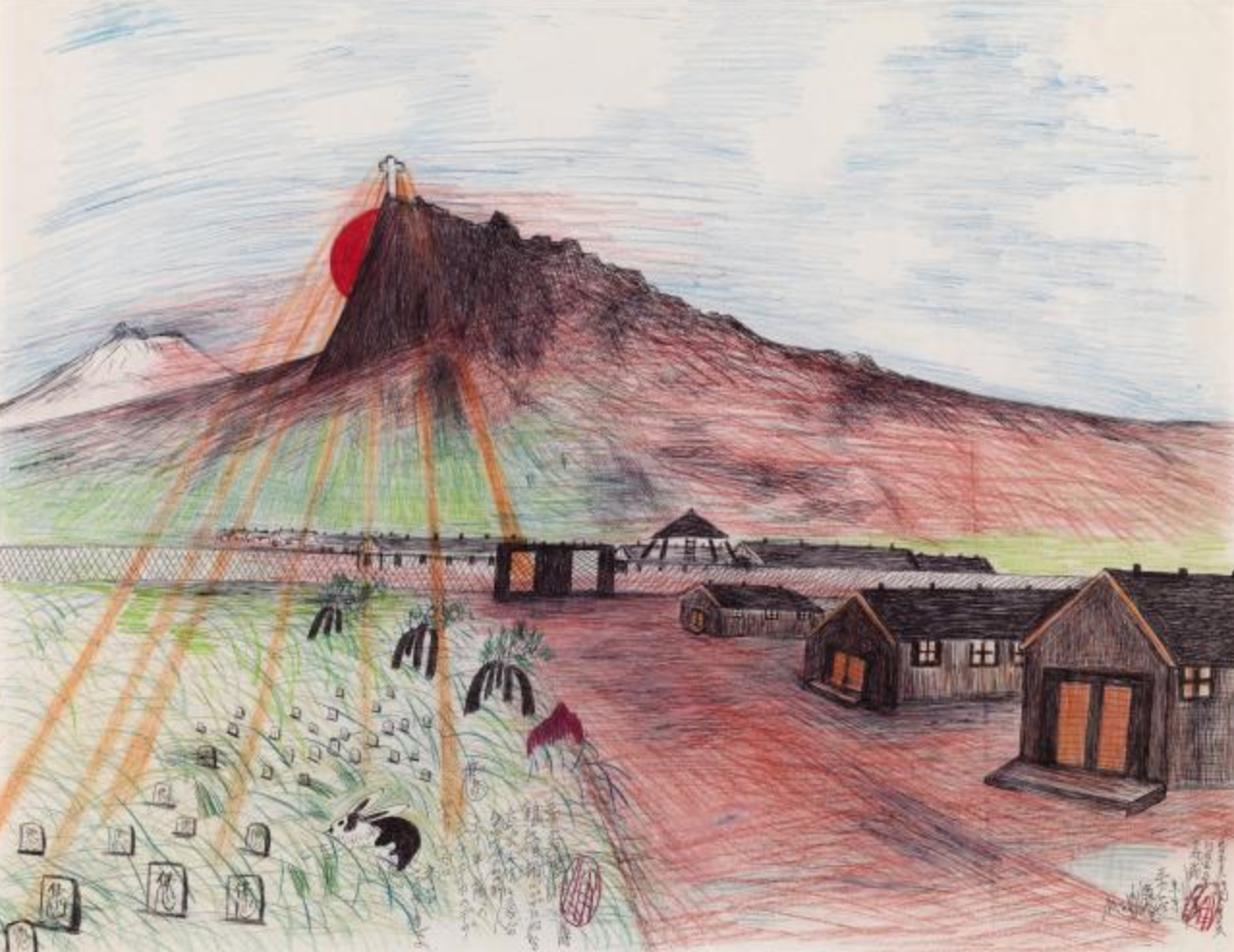

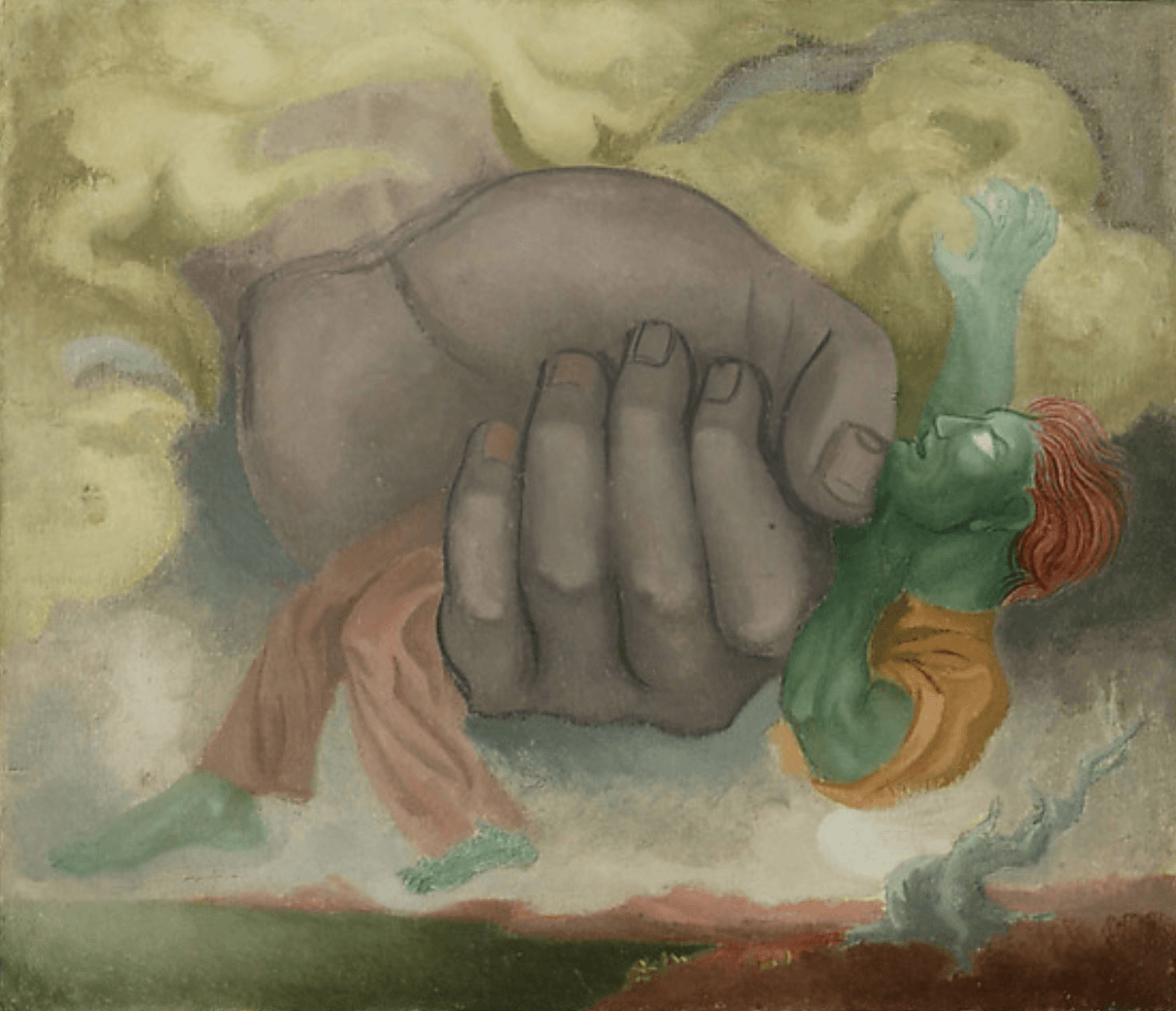

Mirkitani, Jimmy. Cemetary in Tule Lake. 2002.Okubo, Benji. Untitled. 1942.

Chambers, Tim. Anchor Editions. Anchor Editions, 2017, https://anchoreditions.com/blog/dorothea-lange-censored-photographs.

Accessed April 2019.

Hirasuna, Delphine. The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946. New York City, Crown

Publishing, 2005.

Horne, Madison. History. A&E Television Networks, LLC, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/japanese-internment-camp-wwii-photos#&gid=ci023fede82000267d&pid=japanese_internment_camps_getty-615300536. Accessed April 2019.

Quotes courtesy of Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, California.

Kitagaki, Paul. Gambatte! Legacy of an Enduring Spirit. 17 Nov. 2018-28 Apr. 2019, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles.

Shimabukuro, Mira. “Me Inwardly, Before I Dared.” College English, vol. 73, no. 6, 2011, pp. 648-671.