History of the Internment Camps

"A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched- so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents- grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”

-Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1942

“If making one million innocent Japanese uncomfortable would prevent one scheming Japanese from costing the life of one American boy, then let the million innocents suffer… personally, I hate the Japanese and that goes for all of them.”

- Henry McLemore, columnist

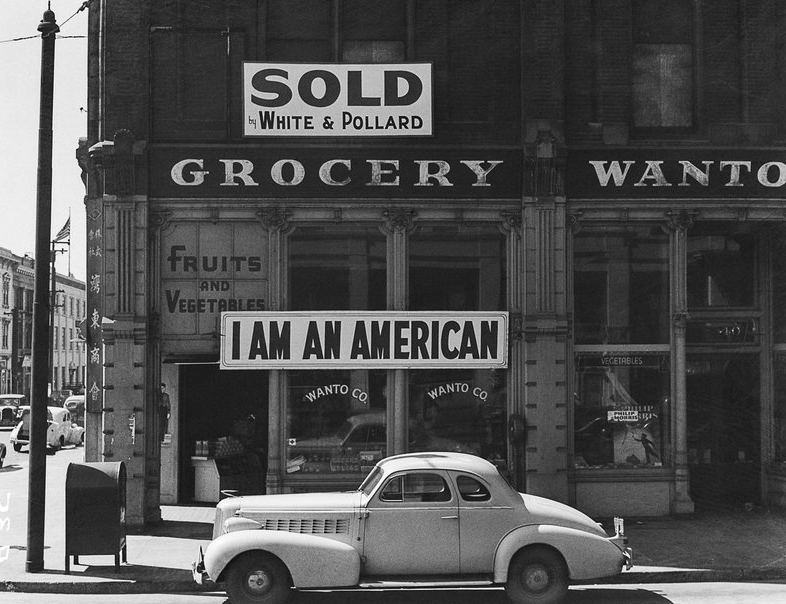

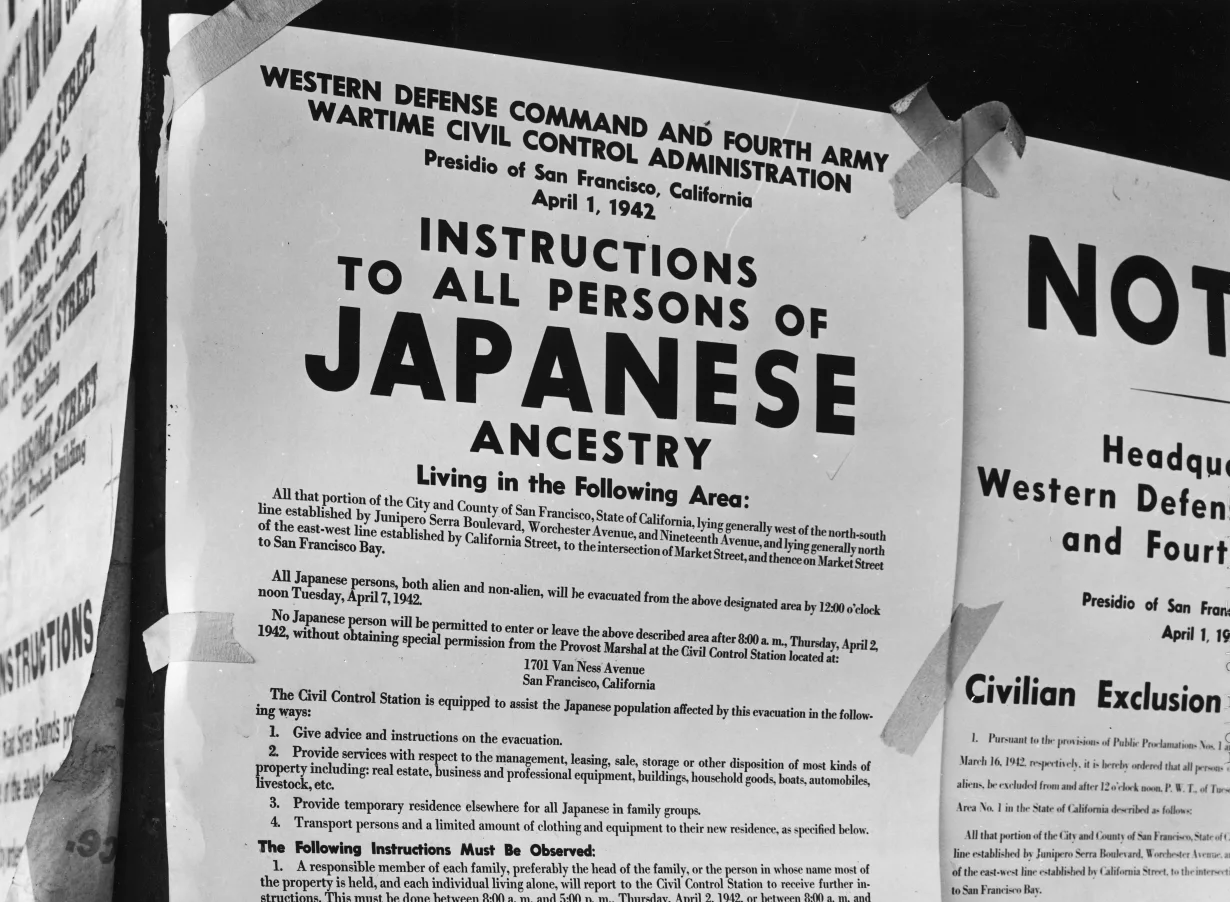

Photos courtesy of Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee

Film created by the War Relocation Authority attempting to defend the massive internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II.

Locations of the 10 War Relocation Authority Camps

All Locations

LIST

MAP

- Topaz Internment Camp W 4500 N, Delta, UT 84624, United States

- Poston Internment Camp La Paz, AZ, United States

- Gila River Internment Camp Gila River Xing, Laveen, Arizona, United States

- Granada (Amache) Internment Camp Granada, CO, United States

- Heart Mountain Internment Camp Park, WY, United States

- Jerome Internment Camp Jerome, Dermott, AR, United States

- Manzanar Internment Camp Manzanar Reward Rd, Independence, 93526, Inyo, California, United States

- Minidoka Internment Camp Jerome, ID 83338 USA

- Rohwer Internment Camp Desha, AR, United States

- Tule Lake Internment Camp Tulelake, CA, United States

Quotes courtesy of:

Densho. Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project, 2017, https://densho.org/. Accessed Apr-May 2019.

Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, California.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chambers, Tim. Anchor Editions. Anchor Editions, 2017, https://anchoreditions.com/blog/dorothea-lange-censored-photographs.

Accessed April 2019.

Hirasuna, Delphine. The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946. New York City, Crown

Publishing, 2005.

Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. New York City, Simon & Schuster, Sept. 2015.

“WWII Japanese Internment Propaganda Film Challenge to Democracy.” Youtube, uploaded by Periscope Film, 19 Nov 2015,

https://www.youtube.com/embed/AFiA8ODu2lM.